Following up on part one, this post contains is a list of science-fiction espionage works I found particularly useful while working on the Imperial Agent. This is by no means an exhaustive inventory of influences (even disregarding non-science-fiction and nonfiction works–and there are plenty of both I could list); it’s simply a rundown of some of the most prominent ones. If you enjoyed the Imperial Agent and the descriptions below pique your interest, consider seeking these works out!

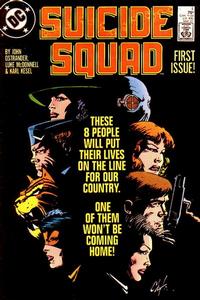

Suicide Squad (John Ostrander and Kim Yale)

Cover images are courtesy of the Grand Comics Database, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

Cover images are courtesy of the Grand Comics Database, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

I expect many readers are familiar with John Ostrander from his work on Star Wars comic books such as Legacy, Dawn of the Jedi, and Agent of the Empire (to name just a few–and we’ll get back to two of those shortly). But while I’d never downplay the significance of his Star Wars work, I still think of him as the man behind The Specter (what can only be described as a theological horror superhero comic), GrimJack (multiversal noir) and Suicide Squad.

Suicide Squad ran for 66 issues (plus annuals and specials) in the late eighties and early nineties. Set in the DC Comics superhero universe, the comic tells the story of a secret department within the US intelligence community that uses imprisoned supervillains for black ops missions. In return for furthering American interests in Colombia, the USSR and occasional alternate dimensions, prisoners receive reduced sentences. The team is overseen by a small group of support personnel and less-than-squeaky-clean superheroes, along with Amanda Waller–“the Wall”–the non-superpowered, middle-aged, overweight woman who was tougher than the rest of the team combined and who spent half her time fighting bureaucrats and congressional investigations.

Suicide Squad remains the single best work of superpowered espionage I’ve encountered. Ostrander–and starting around issue twenty, his co-writer (and wife) Kim Yale–built a morally gray world where psychiatrists and prison wardens worked alongside chronically depressed commanders and superhuman sociopaths. While the squad’s mission objectives were usually respectable (rescuing political dissidents or stopping superpowered terrorists), the squad itself was a corrosive environment. Squad members died or dropped out on a regular basis, as many due to betrayals, psychological problems, and ethical qualms as enemy fire.

Suicide Squad remains the single best work of superpowered espionage I’ve encountered. Ostrander–and starting around issue twenty, his co-writer (and wife) Kim Yale–built a morally gray world where psychiatrists and prison wardens worked alongside chronically depressed commanders and superhuman sociopaths. While the squad’s mission objectives were usually respectable (rescuing political dissidents or stopping superpowered terrorists), the squad itself was a corrosive environment. Squad members died or dropped out on a regular basis, as many due to betrayals, psychological problems, and ethical qualms as enemy fire.

While the relationship between non-powered individuals and superhumans was never a focus of Suicide Squad, the book painted a picture of a world where gods roamed the Earth but someone still needed to do the dirty work. The Imperial Agent influence should be obvious.

Alas, the series is largely unavailable nowadays–approximately the first third of the series is available in collected editions and in digital format on Comixology, but I find the run from the mid-twenties to the mid-fifties to be the most consistent (it takes a while before Ostrander fully finds his footing, around the same time Yale is credited). Nonetheless, even the early issues are worth seeking out, and–if you’re not sold–many other bloggers have written extensively on the series as well (some spoilers in the previous links).

Now, as for Ostrander’s Star Wars work… both Legacy and Agent of the Empire have Imperial spies among their cast. While these books both began after SWTOR development was in progress, I find it personally pleasing to see Ostrander tapping into some of his old Suicide Squad tricks….

The Lensmen Series (E. E. Smith)

Covers courtesy OpenLibrary.org

Covers courtesy OpenLibrary.org

E. E. “Doc” Smith is commonly regarded as the father of space opera as a genre, and his Lensmen series–mostly published in the pulp magazines of the 1930s and 1940s, later collected in six novels–is the grandest of his space operas. It’s fair to say that without Lensmen, there would be no Star Wars–or at least Star Wars as we know it would be unrecognizable. It’s the story of a galactic civilization policed by a force of highly trained, morally upright telepathic guardians drawn from hundreds of different alien races (many of which have utterly inhuman thought processes, but nonetheless share a common virtue) and battling an evil empire wielding an increasingly mad series of superweapons. (The Death Star would fit somewhere in the midrange of Lensmen weaponry.)

In short, it’s a must-read for anyone writing Star Wars. It may be a greater influence on space opera than Lord of the Rings is on epic fantasy, which should say something.

But while I could write thousands of words on the influence (and general wonderfulness) of Lensmen, this article is supposed to be about Imperial Agent-inspiring science-fiction espionage, not Star Wars or space opera generally. Espionage is a relatively small but important part of the Lensmen stories–protagonist Kimball Kinnison frequently goes undercover to get close enough to the enemy for mind-reading, and while his psychic powers make these infiltrations unconventional, they’re no less delightful for it.

But while I could write thousands of words on the influence (and general wonderfulness) of Lensmen, this article is supposed to be about Imperial Agent-inspiring science-fiction espionage, not Star Wars or space opera generally. Espionage is a relatively small but important part of the Lensmen stories–protagonist Kimball Kinnison frequently goes undercover to get close enough to the enemy for mind-reading, and while his psychic powers make these infiltrations unconventional, they’re no less delightful for it.

Military intelligence-gathering and its associated gadgets also play an important role in the Lensmen novels, and it’s fascinating to see what concepts would eventually be reflected in the real world (stealth vehicles rendered radar-invisible and painted black to avoid visual detection) and which ones wouldn’t (x-ray telescopes).

Not pure espionage by any means, but well worth tracking down for those with any interest in the history of space opera. I recommend starting with the third novel, Galactic Patrol, and skipping over any prologue or summary of the preceding books–Triplanetary and First Lensmen, while entertaining, were written after the rest of the series, and as prequels end up spoiling some later plot twists.

Modern readers may resist E. E. Smith’s admittedly rather bombastic style of prose, but his mastery of it is complete–he puts together some of the most readable and engaging purple prose imaginable. One of my favorite moments in the series is a section where Smith parodies his own work–Kinnison, using a cover identity as a science-fiction writer to keep a low profile, produces some truly terrible writing:

Qadgop the Mercotan slithered flatly around the afterbulge of the tranship. One claw dug into the meters-thick armor of pure neutronium, then another. Its terrible xmex-like snout locked on. Its zymolosely polydactile tongue crunched out, crashed down, rasped across. Slurp! Slurp! At each abrasive stroke the groove in the tranship’s plating deepened and Qadgop leered more fiercely. Fools! Did they think that the airlessness of absolute space, the heatlessness of absolute zero, the yieldlessness of absolute neutronium, could stop QADGOP THE MERCOTAN? And the stowaway, that human wench Cynthia, cowering in helpless terror just beyond this thin and fragile wall…

Mercifully, that’s the only passage we see of Kinnison’s novel. But it’s always nice when authors have a sense of humor about their own excesses.

Use of Weapons (Iain M. Banks)

Cover courtesy OpenLibrary.org

Cover courtesy OpenLibrary.org

From the origins of space opera to its modern incarnation: Iain M. Banks is the author of numerous novels set in the universe of “the Culture.” The Culture novels posit a galaxy with many of the familiar space opera tropes–hundreds of alien races, centuries-long wars, massive starships, etc.–but updates it with a layer of nanotechnology, transhumanist thought, and progressive politics (though whether one considers the Culture a utopia or dystopia is a matter of taste).

Use of Weapons is one of several Culture novels dealing heavily with “Special Circumstances”–essentially the Culture’s espionage agency. Special Circumstances agents frequently infiltrate alien societies in order to manipulate them to the Culture’s ends. Such agents often commit horrible crimes and suffer terrible psychological tolls in order to succeed at their missions–and those missions can be gruesome in themselves, if the Culture determines that an enemy civilization or race is essentially irredeemable.

Use of Weapons in particular and the Culture novels as a whole are an excellent example of space opera tropes used in the service of ground-level, human stories. In much of the series, whether planets or galaxies are at stake is largely irrelevant–what matters are the moral and psychological costs involved. (The incomprehensibility of galactic-level stakes for human minds, in fact, is a point that’s never directly addressed to my recollection, but certainly plays a role in characters’ decision-making processes.) For readers interested in dark science-fiction espionage stories set against the backdrop of a wondrous high-tech universe, Use of Weapons should serve nicely.

The Prisoner

Cover of Patrick McGoohan: Danger Man or Prisoner? courtesy OpenLibrary.org

Cover of Patrick McGoohan: Danger Man or Prisoner? courtesy OpenLibrary.org

I’ll happily argue that The Prisoner (starring and co-created by Patrick McGoohan) is one of the great television shows of all time. It’s certainly some of the best science-fiction ever done in the medium. The Prisoner ran for seventeen episodes beginning in 1967 and centers around a British spy who, after resigning from his job, is captured and imprisoned in the mysterious “Village”–an apparently “idyllic” isolated community. The Village is occupied by other former spies and persons with sensitive information, and the people who run the Village (whose allegiance is unclear) use every possible means to dehumanize and break their captives. Villagers are referred to by number, not name–we only know our protagonist as “Number Six.” The leader of the village frequently and inexplicably changes, but is always “Number Two.” No one knows the identity of Number One.

Most episodes of The Prisoner deal with the wardens attempting some new way of breaking Number Six (using methods ranging from trickery to psychotropic drugs) and encouraging him to conform to Village life; or, alternately, Number Six’s latest escape attempt. Sometimes both. Themes of control and rebellion are ever-present, and virtue and conscience are the province of individuals, never organizations.

The Prisoner’s sense of humor is worth noting as well. Sly and sardonic, some of the most entertaining exchanges are between McGoohan’s Number Six and Leo McKern’s Number Two:

For its overall themes and its bizarre assortment of hallucinogenic technologies, The Prisoner easily wins a place on this list. It’s available, in full, on Crackle.com and on Crackle’s YouTube channel (though curiously, some episodes appear to be mislabeled in the latter). I cannot recommend it highly enough.

Aeon Flux

Take the mind games of The Prisoner and put them to use in the service of interpersonal, rather than political themes, then filter the result through a violent, sexy science-fiction world that wouldn’t be out of place in a 2000 AD comic book. Aeon Flux was televised first as a series of animated shorts, then as full-length episodes on MTV during the early 1990s. (Ignore the later live-action film version.)

The eponymous heroine is an amoral anarchist (of sorts) working against (usually) an oppressive regime. While the show’s conceptual depth is considerable, the weird aesthetics and technology are well worth attention as well–Aeon is cloned and killed, meets angelic beings, and keeps insect eggs in her boots in case of emergency. Creator Peter Chung develops a bizarre, fascinating, and horrifying world with a unique science-fiction flavor.

Much of Aeon Flux is available at MTV’s Liquid Television site, and while certainly not to everyone’s taste, it’s worth a look. If episode descriptions and title cards such as “Trevor attempts to shoot a ray that will end human evolution” and “Aeon Flux and the Monican resistance have captured the Demiurge, a powerful god-like being, and prepare to send it into space to rid the Earth of its influence” don’t at least intrigue you (and if you’re willing to give the show a chance to prove that Aeon’s outfit isn’t entirely gratuitous), give a few episodes a try. In any order, really–it doesn’t actually matter.